Tuesday, April 28, 2009

White Matter

The white matter is the whitish nerve tissue of the cerebrum, cerebelum, and spinal cord, consisting chiefly of myelinated axons of nerve cells. Most of the axons are covered by whitish, fatty sheaths called myelin, hence appearing white in freshly-cut brain or spinal cord. The white matter is found in the central part of the brain and is surrounded by the cerebral cortex grey matter. In the spinal cord it is the other way around, the white matter envelops the grey matter.

Grey Matter

The grey matter is the major component of the central nervous system. It consists of neurons bodies, dendrites, non-myelinated axons and myelinated axons, glial cells and capillaries. Grey matter contains neurons bodies, in contrast to white matter, which does not and mostly contains myelinated axon tracts. In living tissue, grey matter actually has a grey-brown color which comes from capillary blood vessels and neuronal cell bodies.

The grey matter is the cerebral cortex and the long H-like bundle found at the center of the spinal cord.

The grey matter is the cerebral cortex and the long H-like bundle found at the center of the spinal cord.

Astrocyte

Astrocytes are star-shaped glial cells which are found in the brain and spinal cord. Astrocytes are the most abundant support cells in the central nervous system and they perform many functions, which includes biochemical support of endothelial cells which form the blood-brain barrier, the provision of nutrients to the nervous tissue, and a principal role in the repair and scarring process of the brain and spinal cord following traumatic injuries.

An astrocyte is a sub-type of the glial cells in the brain and spinal cord. It is also known as astrocytic glial cell. Its processes envelope synapses made by neurons. Astrocytes are classically identified histologically as many of these cells express the intermediate filament glial fibrillary acidic protein.

There are three types of astrocytes in the Central Nervous System, fibrous, protoplasmic, and radial. The fibrous glial cells are usually located within white matter, have relatively few organelles, and exhibit long unbranched cellular processes. This type has "vascular feet" that physically connect the cells to the outside of capillary wall when they are in close proximity of them. The protoplasmic astrocytes are found in grey matter tissue, possess a larger quantity of organelles, and exhibit short and highly branched cellular processes. Finally, the radial astrocytes are disposed in a plane perpendicular to axis of ventricles.

Teledendria

Teledendria, or telodendria, are the branched thin tree-like filaments found at the end of an axon. Each one of these teledendria is called teledendron, which secretes neurotransmitters that act on the dendrites or cell bodies of other neurons via synapses.

The teledendria have terminal buttons at their tip that are called "boutones terminaux" which contain neurotransmitters.

Dendrite

Dendrites are the branched, tree-like protoplasmatic filaments of a neuron that conduct the electrochemical impulses towards the body of the nerve cell. These impulses are received from other neurons through their axons via synapses. The dendrite impulse towards the center of the neuron's body is called "centripetal" signal. A single nerve cell, or neuron, may have many dendrites.

Monday, April 27, 2009

Neurilemma

Neurilemma is the outermost cytoplasmic layer of Schwann cells that surrounds the axon of the neuron. It forms the outermost layer of the nerve fiber in the peripheral nervous system. The neurilemma is underlain by the basal lamina. It is important to note that in the Central Nervous System, axons are myelinated by oligodendrocytes, thus lack neurilemma.

Myelin

Myelin is the sheath of fatty protein which surrounds the axon of a neuron. Myelin considerably increases the speed of the nerve signals which move down the axons. Myelin is produced by glial cells such as Oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells.

Myelin gives axons the white appearance, thus the "white matter" of the brain. Myelin is composed of about 80% lipid and about 20% protein. Some of the proteins that make up myelin are Myelin basic protein, Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein, and Proteolipid protein.

Oligodendrocytes

Oligodendrocytes are a type of glial cells whose main function is to insulate the axons in the central nervous system of the higher vertebrates. A single oligodendrocyte can reach to up to 50 axons, wrapping around approximately 1 mm of each and forming the myelin sheath.

Oligodendrocytes are responsible for producing a myelin, which insulates axons. Oligodendrocytes wrap the myelin around the axons in thin sheets like rolled up paper, nourishing and supporting them.

Glial Cells

Glial cells, or neuroglia, are non-neuronal, supporting cells which surround neurons and their axons to provide support, nutrition, and electrical insulation between neurons. They form myelin, and participate in signal transmission in the nervous system. In the human brain, there is about one glia cell for every neuron with a ratio of about two neurons for every three glia cells in the cerebral gray matter.

The neuroglia cells are thus known as the "glue" of the nervous system. The five main functions of glial cells are to surround neurons and hold them in place, to supply nutrients and oxygen to neurons, to insulate one neuron from another, and to destroy pathogens and remove dead neurons, to modulate neurotransmission. There are four types of glia cells: Astrocytes, Oligodendrocytes, and Microglia in the Central Nervous System; Schwann cells in Peripheral Nervous System.

Schwann Cells

Schwann cells are a type of glial cells which wraps themselves around myelinated and non-myelinated axons to keep them alive, nourishing and protecting them. In myelinated axons, Schwann cells form the myelin sheath. This fatty sheath is not continuous. Individual myelinating Schwann cells cover about 100 micrometers of an axon. As a result, there is a string of Schwann cells along the length of the axon, much like a string of sausages. The gaps or space between adjacent Schwann cells are known as the nodes of Ranvier. Non-myelinating Schwann cells are involved in maintenance of axons and are crucial for neuronal survival.

Sunday, April 26, 2009

Axon

An axon is a long, slender process which projects from a neuron's body and conducts electrical impulses away from the neuron's cell body to another neuron's dendrite or organ. It is also called nerve fiber. An axon can be more than three feet long and at the end of which it branches to form a tree like structure called teledendria that produce neurotransmitters.

Each axon is covered in a fatty substance called myelin, which nourishes and protects it. The myelin is formed by either of two types of glial cells: Schwann cells wraps around peripheral neurons axons, and oligodendrocytes cells which insulate those of the central nervous system. There are gaps along these myelinated nerve fibers called nodes of Ranvier. Axons usually runs along in groups or bundles called nerves.

Each axon is covered in a fatty substance called myelin, which nourishes and protects it. The myelin is formed by either of two types of glial cells: Schwann cells wraps around peripheral neurons axons, and oligodendrocytes cells which insulate those of the central nervous system. There are gaps along these myelinated nerve fibers called nodes of Ranvier. Axons usually runs along in groups or bundles called nerves.

Nervous System

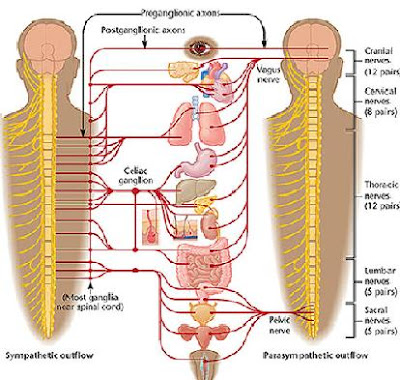

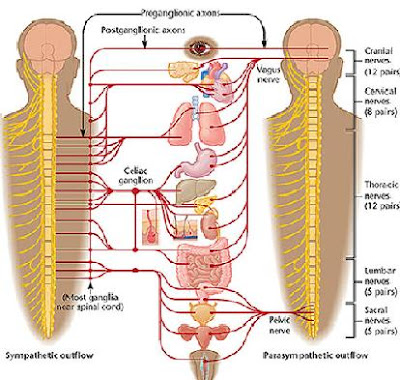

The nervous system is a system of nerve cells, tissues, and organs which regulates the body's responses to internal and external stimuli through nervous impulses that travel fast through a complex network of cable-like nerves. In vertebrates it is composed of the brain, spinal cord, nerves, ganglia, and parts of the receptor and effector organs.

The nervous system is divided into three categories: the central nervous system; the peripheral nervous system; and autonomic nervous system. The central nervous system is made up of the brain, the cerebelum, and spinal cord, and is encased in the cranium and spinal column. The peripheral nervous system is composed of the long cable-like nerves that connect sensory nerve cells, to the spinal cord and brain. The autonomi nervous system is the part of the nervous system which regulates involuntary action, as of the liver, pancreas, intestines, heart, and glands.

The nervous system is divided into three categories: the central nervous system; the peripheral nervous system; and autonomic nervous system. The central nervous system is made up of the brain, the cerebelum, and spinal cord, and is encased in the cranium and spinal column. The peripheral nervous system is composed of the long cable-like nerves that connect sensory nerve cells, to the spinal cord and brain. The autonomi nervous system is the part of the nervous system which regulates involuntary action, as of the liver, pancreas, intestines, heart, and glands.

Saturday, April 25, 2009

Bacitracin

Bacitracin is a polypeptide antibiotic obtained from a strain of a bacterium (Bacillus subtilis) and used as a topical ointment in the treatment of certain bacterial infections, especially those caused by cocci. Since it is toxic, bacitracin is widely used for topical therapy such as for skin and eye infections. It is effective against gram-positive bacteria, including strains of staphylococcus that are resistant to penicillin.

Polypeptide Antibiotics

Polypeptide antibiotics are a group of antibiotics which is used in the treatment of eye, ear, and bladder infections in addition to aminoglycosides. Since they are toxic, polypeptides are not suitable for systemic administration. They are only administered topically on the skin. They are usually applied directly to the eye or inhaled into the lungs. It is not given by injection. Their mechanism of action is protein inhibition, but is largely unknown.

Polypeptide antibiotics adverse effects are kidney and nerve damage when administered by injection. Polypeptides include actinomycin, bacitracin, colistin, polymyxin B.

Polypeptide antibiotics adverse effects are kidney and nerve damage when administered by injection. Polypeptides include actinomycin, bacitracin, colistin, polymyxin B.

Carbenicillin

Carbenicillin is a bactericidal antibiotic which belongs to the group of the penicillins. It destroy gram-negative bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa by preventing bacterial cell wall synthesis, inhibiting crosslinking of peptidoglycan by binding and inactivating transpeptidases. The carboxypenicillins are susceptible to degradation by beta-lactamase enzymes, although they are more resistant than ampicillin to degradation. Carbenicillin is also more stable at lower pH than ampicillin.

Carbenicillin is effective in the treatment of infections caused by certain susceptible strains of Gram-negative bacteria, such as Pseudomonas and Proteus.

Friday, April 24, 2009

Azlocillin

Azlocillin is a semisynthetic, broad-spectrum, bactericidal antibiotic which belongs to the group of penicillins. Azlocillin is an acylampicillin which binds to penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs) located inside the bacterial cell wall, thereby inhibiting the cross-linking of peptidoglycans, which are critical components of the bacterial cell wall. This prevents proper bacterial cell wall synthesis, thereby results in the weakening of the bacterial cell wall and eventually leading to cell lysis.

Azlocillin is prescribed for the treatment of lower respiratory tract, urinary tract, skin, bone, and joint infections, and bacterial septicemia caused by susceptible strains of microorganisms, mainly Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Ampicillin

Ampicillin is a beta-lactam bactericidal antibiotic which belong to the penicillin group. It has been used extensively to treat bacterial infections since 1961. Ampicillin is able to penetrate Gram-positive and some Gram-negative bacteria and destroy it from within.

Ampicillin is widely used for treating various types of infections that are usually caused by bacteria like ear infection, bladder infection, pneumonia, gonorrhea as well as E. coli or salmonella infections. It is sold in the UK under the brand name Omnipen, and in the US Principen, both for oral administration.

Amoxicillin

Amoxicillin is a bactericidal penicillin antibiotic which is used in the treatment of many different types of infections caused by bacteria, such as ear infections, bladder infections, pneumonia, gonorrhea, and E. coli or salmonella infection.

Amoxicillin, a semisynthetic antibiotic, is an analog of ampicillin, with a broad spectrum of bactericidal activity against many gram-positive and gram-negative microorganisms. Amoxicillin acts by inhibiting the synthesis of bacterial cell wall. It inhibits cross-linkage between the linear peptidoglycan polymer chains that make up a major component of the cell wall of Gram-positive bacteria. Amoxicillin is administered orally.

Thursday, April 23, 2009

Rapamycin

Rapamycin is an antibiotic that blocks a protein involved in cell division and inhibits the growth and function of certain T cells of the immune system involved in the body's rejection of foreign tissues and organs. It is a type of immunosuppressant and a type of serine/threonine kinase inhibitor. Rapamycin is now called sirolimus.

Rapamycin, or sirolimus (INN), is an immunosuppressant drug used to prevent rejection in organ transplantation. It is especially useful in kidney transplants. Sirolimus is a macrolide and was first discovered as a product of the bacterium Streptomyces hygroscopicus.

Penicillin

Penicillin is a group of broad spectrum antibiotics derived from Penicillium fungi. Today penicillins are produced synthetically. They are bactericidal and are most active against gram-positive bacteria and used in the treatment of various infections and diseases.

Penicillin was discovered by the Scottish scientist and nobel laureate Alexander Fleming in 1928. He showed that if Penicillium notatum was grown in the appropriate substrate, it would exude a substance with antibiotic properties. Ampicillin and Amoxicillin are the most widely used penicillins.

Penicillins are Beta-lactam antibiotics used in the treatment of bacterial infections caused by susceptible, usually Gram-positive, organisms. The term "penicillin" can also refer to the mixture of substances that are naturally produced. The term Penam is used to describe the core skeleton of a member of a penicillin antibiotic. This skeleton has the molecular formula R-C9H11N2O4S, where R is a variable side chain.

Penicillins are sometimes combined with other ingredients called beta-lactamase inhibitors, which protect the penicillin from bacterial enzymes that may destroy it before it can do its work.

Penicillin was discovered by the Scottish scientist and nobel laureate Alexander Fleming in 1928. He showed that if Penicillium notatum was grown in the appropriate substrate, it would exude a substance with antibiotic properties. Ampicillin and Amoxicillin are the most widely used penicillins.

Bactericidal Antibiotics

Bactericidal antibiotics are antibiotics which kill bacteria through direct action, usually by causing the cells to split open, or lyse. Most bactericidal antibiotics work by altering the biochemical pathway through which bacteria make the cell wall. As the antibiotic is taken into the cell, it stops the biochemical machinery of the cell producing or attaching one the major components of cell wall structure.

The cell wall produced is thinner than usual. As the cell divides, the two daughter cells then also have weaker cell walls and they cannot strengthen them because they are also prevented from making all of the necessary components. As they try to divide subsequently, the cell walls of these daughter bacteria fail. Lysis of the cell follows and the bacterium dies. Penicillin antibiotics work in this way, as do the cephalosporins.

The cell wall produced is thinner than usual. As the cell divides, the two daughter cells then also have weaker cell walls and they cannot strengthen them because they are also prevented from making all of the necessary components. As they try to divide subsequently, the cell walls of these daughter bacteria fail. Lysis of the cell follows and the bacterium dies. Penicillin antibiotics work in this way, as do the cephalosporins.

Bacteriostatic Antibiotics

Bacteriostatic antibiotics inhibit growth and reproduction of bacteria without killing them. Bacteriostatic antibiotics does not kill, but limit the growth of bacteria by interfering with bacterial protein production, DNA replication, or other aspects of bacterial cellular metabolism.

Dirithromycin

Dirithromycin is a macrolide antibiotic. It used in the treatment of mild to moderate upper and lower respiratory tract infections due to Moraxella catarrhalis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila, H. influenzae, or S. pyogenes, ie, acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis, secondary bacterial infection of acute bronchitis, community-acquired pneumonia, pharyngitis/tonsillitis, and uncomplicated infections of the skin and skin structure due to Staphylococcus aureus.

Dirithromycin is a more lipid-soluble prodrug derivative of 9S-erythromycyclamine prepared by condensation of the latter with 2-(2-methoxyethoxy)acetaldehyde. The 9N, 11O-oxazine ring thus formed is a hemi-aminal that is unstable under both acidic and alkaline aqueous conditions and undergoes spontaneous hydrolysis to form erythromycyclamine. Erythromycyclamine is a semisynthetic derivative of erythromycin in which the 9-ketogroup of the erythronolide ring has been converted to an amino group.

Dirithromycin brand name is Dynabac.

Dirithromycin is a more lipid-soluble prodrug derivative of 9S-erythromycyclamine prepared by condensation of the latter with 2-(2-methoxyethoxy)acetaldehyde. The 9N, 11O-oxazine ring thus formed is a hemi-aminal that is unstable under both acidic and alkaline aqueous conditions and undergoes spontaneous hydrolysis to form erythromycyclamine. Erythromycyclamine is a semisynthetic derivative of erythromycin in which the 9-ketogroup of the erythronolide ring has been converted to an amino group.

Dirithromycin brand name is Dynabac.

Erythromycin

Erythromycin is a macrolide antibiotic which is used when the patient has an allergy to penicillins, for it has an antimicrobial spectrum similar to penicillin. It used in the treatment of respiratory tract infections, and has better coverage of atypical organisms, including mycoplasma and Legionellosis. It is no longer recommended by the American Heart Association and the American Dental Association for treatment of bacterial endocarditis in patients hypersensitive to penicillin.

Erythromycin is a macrocyclic compound which contains a 14-membered lactone ring with ten asymmetric centers and two sugars (L-cladinose and D-desoamine), which makes it very difficult to produce via synthetic methods. Erythromycin is produced from a strain of the actinomycete Saccharopolyspora erythraea, formerly known as Streptomyces erythraeus. It is administered orally under the brand name of Eryc.

Clarithromycin

Clarithromycin is a semi-synthetic macrolide antibiotic that is used in the treatment of pharyngitis, tonsillitis, acute maxillary sinusitis, acute bacterial exacerbation of chronic bronchitis, atypical pneumonias associated with Chlamydia pneumoniae, skin and skin structure infections, and, in HIV and AIDS patients to prevent, and to treat, disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex. In addition, it is also used to treat Legionellosis and lyme disease.

Clarithromycin is available under several brand names such as Biaxin and Klaricid. Chemically, it is 6- 0-methylerythromycin. The molecular formula is C38H69NO13, and the molecular weight is 747.96.

Azithromycin

Azithromycin is a semi-synthetic macrolide antibiotic, which is chemically related to erythromycin and clarithromycin. It is used in the treatment of infections caused by a wide variety of bacteria such as Hemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, mycobacterium avium, and many others. Azithromycin prevents bacteria from growing by interfering with their ability to make proteins. Due to the differences in the way proteins are made in bacteria and humans, the macrolide antibiotics do not interfere with production of proteins in humans.

Azithromycin is commonly administered in tablet or oral suspension. It is also available for intravenous injection and in a 1% ophthalmic solution. Tablets come in 250 mg and 500 mg doses. It is sold under the brand name Zithromax.

Tuesday, April 21, 2009

Macrolide

A macrolide is class of antibiotics discovered in Streptomyces. It is characterized by molecules made up of large-ring lactones. An example is erythromycin. A macrolide works by inhibiting protein synthesis.

Macrolides are considered bacteriostatic at therapeutic concentrations, but they can be slowly bactericidal, especially against streptococcal bacteria; their bactericidal action is described as time-dependent. The antimicrobial action of some macrolides is enhanced by a high pH and suppressed by low pH, making them less effective in abscesses, necrotic tissue, or acidic urine.

Macrolides are used in the treatment of infections such as respiratory tract and soft tissue infections. The antimicrobial spectrum of macrolides is slightly wider than that of penicillin, and therefore macrolides are a common substitute for patients with a penicillin allergy.

Macrolides are considered bacteriostatic at therapeutic concentrations, but they can be slowly bactericidal, especially against streptococcal bacteria; their bactericidal action is described as time-dependent. The antimicrobial action of some macrolides is enhanced by a high pH and suppressed by low pH, making them less effective in abscesses, necrotic tissue, or acidic urine.

Macrolides are used in the treatment of infections such as respiratory tract and soft tissue infections. The antimicrobial spectrum of macrolides is slightly wider than that of penicillin, and therefore macrolides are a common substitute for patients with a penicillin allergy.

Cefixime

Cefixime is a semisynthetic, third generation cephalosporin antibiotic for oral administration. It is used in the treatment of gonorrhea,tonsilitis, and pharyngitis. Cefixime is sold under the trade name Suprax in the USA.

Cefaclor

Cefaclor is a second-generation cephalosporin antibiotic which is used in the treatment of ear, lung, skin, throat, and urinary tract infections as well as pneumonia. Allergic reactions may arise as side effects, for example, rashes, itching, urticaria, serum sickness-like reactions with rashes, fever and arthralgia, and anaphylaxis.

Cefaclor is a semisynthetic antibiotic for oral administration. It is chemically designated as 3-chloro-7-D-(2-phenylglycinamido)-3-cephem-4-carboxylic acid monohydrate. The chemical formula for cefaclor is C15H14ClN304S•H2O and the molecular weight is 385.82.

Cefaclor is a semisynthetic antibiotic for oral administration. It is chemically designated as 3-chloro-7-D-(2-phenylglycinamido)-3-cephem-4-carboxylic acid monohydrate. The chemical formula for cefaclor is C15H14ClN304S•H2O and the molecular weight is 385.82.

Cefalexin

Cefalexin is a broad spectrum, first generation Cephalosporin antibiotic, which is active against a wide variety of bacteria. Cefalexin is a bactericidal antibiotic which works by killing and stopping the growth of the bacteria that cause infections.

Cefalexin is used in the treatment of urinary tract infections, respiratory tract infections such as sinusitis, otitis media, pharyngitis, tonsillitis, pneumonia, and bronchitis, and skin and soft tissue infections.

Monday, April 20, 2009

Cefazolin

Cefazolin is a bactericidal antibiotic which belong to the cephalosporin group of antibiotics; it is a first generation cephalosporin. Cefazolin is usually administrated either by intramuscular injection or intravenous infusion. It is used in the treatment of infections of the skin, bone, heart, blood, respiratory tract, sinuses, ear, and urinary tract. When it is given before surgery, cefazolin is also useful in preventing infection during surgery.

Cefadroxil

Cefadroxil is a broad-spectrum, bactericidal antibiotic which is effective against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial infections. It is also known as Curisafe. Cefadroxil is a first generation cephalosporin.

Cefadroxil is used against infections of the urinary tract, skin and soft- tissue, pharynx (throat), and tonsillitis caused by bacteria that are susceptible to its effects such as the bacteria Streptococcus pyogenes.

Cefadroxil is used against infections of the urinary tract, skin and soft- tissue, pharynx (throat), and tonsillitis caused by bacteria that are susceptible to its effects such as the bacteria Streptococcus pyogenes.

Cephalosporins

The cephalosporins are broad-spectrum antibiotics, which are closely related to the penicillins. They were originally derived from the fungus Cephalosporium acremonium. Cephalosporins are bactericidal and, like beta-lactam antibiotics such as penicillins, they disrupt the synthesis of the peptidoglycan layer of bacterial cell walls.

Cephalosporins are classified in groups called "generations" by their antibactericidal properties. The first cephalosporins were designated first generation. Later, more extended spectrum cephalosporins were classified as second-generation cephalosporins. Each newer generation of cephalosporins has significantly greater Gram-negative antibactericidal properties than the preceding generation.

Sunday, April 19, 2009

Sartorius Muscle

The Sartorius muscle is a long thin muscle that runs down diagonally the length of the thigh. It is the longest muscle in the human body. Its upper portion forms the lateral border of the femoral triangle. The sartorius muscle originates from tendinous fibers from the anterior superior iliac spine, running obliquely across the upper and anterior part of the thigh in an inferomedial direction, descending as far as the medial side of the knee and passing behind the medial condyle of the femur to end in a tendon.

The Sartorius muscle is innervated by the femoral nerve. It flexes, abducts, and laterally rotates thigh and hip.

Pectoralis Major

The Pectoralis major, or pectoral muscle, is a fan-shaped muscle, located at the upper front of the chest wall. It constitutes the bulk of the chest muscles in the male and lies under the breast in the female. The Pectoralis major is innervated by the lateral pectoral nerve and the medial pectoral nerve, pulling the arm across the chest, rotating it inwards as it contracts.

The Pectoralis major is divided into two heads: 1) the clavicular head originates at anterior surface of the medial half of the clavicle; 2) the sternocostal head arises from anterior surface of the sternum, the superior six costal cartilages, and the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle. The pectoral muscle is inserted in the intertubercular groove of the humerus (upper arm bone).

Deltoid Muscle

The deltoid muscle is a thick, flat triangular muscle which forms the round shape of the shoulder. One end is attached to the collar bone and shoulder blade, and the other to the humerus bone in the arm. The name derives from the shape of the Greek letter Delta (triangle). The deltoid is an antagonist muscle of the pectoralis major and latissimus dorsi during arm adduction.

The deltoid takes part in the movements of the upper arm, lifting the arm sideways away from the midline of the body. The deltoid main actions are flexion and horizontal adduction of the humerus (upper arm bone); those of the middle fibers are abduction and horizontal abduction; and those of the posterior fibers are extension and horizontal abduction.

The deltoid muscle has three sections, the front head, the side head and the rear head, and is innervated by the axillary nerve. Weight training exercises for strengthening the deltoid muscle include dumbbell curls, the dumbbell punch, and the military press.

Saturday, April 18, 2009

Skeletal Muscle

Skeletal muscle is voluntary muscle which consists of elongated, multinucleated, and transversely striated muscle cells. Skeletal muscle cells are called fibers, which group together into bundles called fascicles, which are wrapped in the epimysium to form a skeletal muscle such as the deltoid, or one portion of the biceps.

When skeletal muscle contracts, it effects skeletal movement. The contraction is caused by nervous signals sent by either the brain cortex or the spinal cord through the nerves.

Perimysium

Perimysium is a layer of connective tissue which ensheathes individual muscle fibers into bundles called fascicles. The perimysium plays a role in transmitting lateral contractile movements.

Epimysium

Epimysium is a layer of connective tissue which wraps around an entire muscle. It is continuous with fascia and other connective tissue muscle sheaths, which encludes the endomysium, and perimysium. It is also continuous with tendons where it becomes thicker and collagenous. The Epimysium protects muscles from friction against other muscles and bones.

Endomysium

The endomysium is a layer of connective tissue which wraps around a muscle fiber. It also contains capillaries, nerves and lymphatics.

Friday, April 17, 2009

Fascicle (Muscle Anatomy)

A muscle fascicle is a bundle of muscle fibers surrounded by perimysium, a type of dense connective tissue.

Sarcomere

A sarcomere is one of the segments into which a myofibril of striated muscle is divided. It is smallest functional unit of a muscle. The sarcomere is a functional unit composed of two membranes (Z-lines), which act as boundaries. The Z-lines are attachment points of actin filaments, while the M-band/line is where the myosin filaments attach. The muscle contraction is a result of the actin and myosin filaments sliding over each other, thereby causing the length of the sarcomere to shorten.

Muscle

Muscle is the body contractile tissue which moves the skeleton and makes it possible for the heart to pump blood. It is composed of muscle cells called fibers whose main property is elasticity. Muscle fibers are bound together by perimysium into bundles called fascicles which are grouped together to form muscle. The muscle is enclosed in a sheath of epimysium. Each fiber is made up of myofibrils, which contain sarcomeres. Sarcomeres are composed of actin and myosin. Individual fibers are surrounded by endomysium.

There are three types of muscle: skeletal, cardiac, and smooth. Skeletal muscle is anchored to bone by tendons; its contraction effects skeletal locomotion and keeps posture. Cardiac muscle is the heart muscle, which is involuntary; it contracts to pump blood throughout the body. Smooth muscle is the involuntary muscle found within the walls of organs and structures such as the liver, kidney, esophagus, stomach, blood vessels, uterus, etc.

Thursday, April 16, 2009

Omega Centauri (NGC 5139)

Omega Centauri (NGC 5139) is a globular cluster in the constellation of Centaurus. It is the biggest of globular clusters of the Milky Way galaxy. The stars of this cluster formed over a 12-billion-year period of time, with several starburst peaks.

Omega Centauri is situated about 18,300 light-years away from Earth and contains several million Population II stars. The stars in its center are very crowded and they are believed to be only 0.1 light years away from each other. NGC 5139 has a total mass of five million Suns and its stars are gravitationally bound into a spherical configuration, with the highest density of stars at the center. Omega Centauri was discovered by Edmond Halley in 1677 who listed it as a Nebula.

M96 Group

The M96 Group is the Leo I Group, which is a group of galaxies in the constellation Leo. It contains between 8 and 24 galaxies, and includes three Messier objects. The group is one of many groups that lies within the Virgo Supercluster. Using the Hubble Space Telescope, 8 Delta Cephei variable stars were found in the brightest galaxy of the group, M96, and were able to derive its distance from the Cepheid period-luminosity relation: M96 is 231+/-13 times more remote from us than the Large Magellanic Cloud, thus 12.7+/-0.8 Mpc (41+/-2 million light years).

Carina Dwarf

The Carina Dwarf Spheroidal is a dwarf galaxy which is satellite to the Milky Way from which it is receding at 230 km/s. The Carina Dwarf was discovered in 1977 with the UK Schmidt Telescope. It may have formed several billion years after the formation of the other satellite galaxies of the Milky Way. Its older stars are younger than 7 billion years.

M32

M32 is a dwarf elliptical galaxy of only about 3 billion solar masses, and a linear diameter of some 8,000 light years, which is very small compared to its giant spiral-shaped neighbor the Andromeda galaxy. It is a member of the Local Group. The M32 is located 2.65 million light years away in the constellation Andromeda.

Tidal effects trigger a massive star burst in the core of the M32, which explains its high density. The M32 has an outer disk.

Wednesday, April 15, 2009

Draco Dwarf

The Draco Dwarf is a spheroidal galaxy which is situated in the direction of the Draco Constellation at 34.6°. It belongs to the Local Group and is a satellite galaxy of the Milky Way galaxy. The Draco Dwarf was discovered by Albert George Wilson of Lowell Observatory in 1954.

It is one of the faintest companions to our Milky Way. The Draco Dwarf galaxy may potentially hold large amounts of dark matter.

Messier M54

Messier M54 (NGC 6715) is a conspicuous globular cluster, which was discovered by Charles Messier on July 24, 1778. It is about 85,000 light years away from the Solar System and is situated in the Sagittarius Dwarf Elliptical Galaxy which belongs to the Local Group of galaxies. The M54 is one of the most luminous known globular clusters with an absolute visual magnitude M_v of -10.01, a brilliance of about 850,000 suns like ours. It is outshined only by the spectacular Omega Centauri in our Milky Way.

Sagittarius Dwarf Elliptical Galaxy

The Sagittarius Dwarf Elliptical Galaxy is an elliptical galaxy that belongs to the Local Group and is satellite of the Milky Way. It is roughly 10,000 light-years in diameter, and is about 70,000 light-years away from Earth. The Sagittarious Dwarf Spheroidal Galaxy travels in a polar orbit at a distance of about 50,000 light-years from the core of the Milky Way. It contains the brightest globular cluster known in the universe, the Messier M54.

Tuesday, April 14, 2009

NGC 1818

NGC 1818 is a young globular cluster that is estimated to be about 40 million years old. All known globulars, except for the NGC 1818, have their age estimated to be between 4-14 billion years. It is part of the Large Magellanic Cloud. Astronomers have found a young white dwarf star in its center. It has recently formed following the burnout of a red giant. The NGC has mass ~3×104 Msun.

Tarantula Nebula (NGC 2070)

The Tarantula Nebula (NGC 2070) is a giant star forming region (H II region) in the Large Magellanic Cloud. It is more than 1,000 light-years in diameter and 180,000 light years away from the Solar System. The Tarantula Nebula is an extremely luminous non-stellar object.

Within the Tarantula (NGC 2070), intense radiation and stellar winds gush out from the central young cluster of massive stars, cataloged as R136, energizing the nebular glow and shaping the spidery filaments. The Tarantula Nebula NGC 2070 was first cataloged as a star, 30 Doradus, but Nicolas Louis de Lacaille recognized its nebular nature in 1751.

Canis Major

The Canis Major dwarf galaxy is an irregular dwarf galaxy which neighbors the Milky Way and belong to the Local Group. It contains about one billion stars with high percentage of red giant stars. Canis Major dwarf galaxy is located about 25,000 light-years away from our Solar System.

The Canis Major dwarf galaxy main body is degraded and tidal disruption causes a long filament of stars to trail behind it as it orbits the Milky Way. It forms a complex ringlike structure sometimes referred to as the Monoceros Ring which wraps around our galaxy three times.

The Canis Major dwarf galaxy main body is degraded and tidal disruption causes a long filament of stars to trail behind it as it orbits the Milky Way. It forms a complex ringlike structure sometimes referred to as the Monoceros Ring which wraps around our galaxy three times.

Monday, April 13, 2009

Eagle Nebula (M16)

The Eagle Nebula (M16) is a young open cluster of stars in the constellation Serpens. It was discovered by Jean-Philippe de Cheseaux in 1745-46. Its shape is reminiscent of an eagle. The Eagle Nebula is the subject of a famous photograph by the Hubble Space Telescope, showing pillars of star-forming gas and dust within the nebula.

The Eagle Nebula lies about 6,500 light years away from the earth.

Dark Matter

Dark matter is hypothetical matter which can not be detected by its emitted radiation. Its presence can only be inferred from gravitational effects on visible matter. The flat rotation curves of spiral galaxies and other evidence of "missing mass" in the universe is due to dark matter.

Dark matter accounts for the rotational speeds of galaxies, orbital velocities of galaxies in clusters, gravitational lensing of background objects by galaxy clusters such as the Bullet Cluster, and the temperature distribution of hot gas in galaxies and clusters of galaxies, playing a central role in galaxy evolution. It also has measurable effects on the anisotropy of the cosmic microwave background. All these lines of evidence suggest that galaxies, clusters of galaxies, and the universe as a whole contain far more matter than that which interacts with electromagnetic radiation.

The dark matter component has much more mass than the visible component of the universe. At present, the density of ordinary baryons and radiation in the universe is estimated to be equivalent to about one hydrogen atom per cubic meter of space. Only about 4% of the total energy density in the universe can be seen directly. About 22% is thought to be composed of dark matter.

Dark matter accounts for the rotational speeds of galaxies, orbital velocities of galaxies in clusters, gravitational lensing of background objects by galaxy clusters such as the Bullet Cluster, and the temperature distribution of hot gas in galaxies and clusters of galaxies, playing a central role in galaxy evolution. It also has measurable effects on the anisotropy of the cosmic microwave background. All these lines of evidence suggest that galaxies, clusters of galaxies, and the universe as a whole contain far more matter than that which interacts with electromagnetic radiation.

The dark matter component has much more mass than the visible component of the universe. At present, the density of ordinary baryons and radiation in the universe is estimated to be equivalent to about one hydrogen atom per cubic meter of space. Only about 4% of the total energy density in the universe can be seen directly. About 22% is thought to be composed of dark matter.

Magnetohydrodynamics

Magnetohydrodynamics is the scientific discipline which studies the dynamics of electrically conducting fluids, which include liquid metals, plasmas, and salt water. The field of magnetohydrodynamics was started by Hannes Alfvén, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1970.

The idea of magnetohydrodynamics is that magnetic fields can induce currents in a moving conductive fluid, creating forces on the fluid, and changing the magnetic field itself. The set of equations which describe magnetohydrodynamics are a combination of the Navier-Stokes equations of fluid dynamics and Maxwell's equations of electromagnetism. These differential equations must to be solved simultaneously, either analytically or numerically.

The idea of magnetohydrodynamics is that magnetic fields can induce currents in a moving conductive fluid, creating forces on the fluid, and changing the magnetic field itself. The set of equations which describe magnetohydrodynamics are a combination of the Navier-Stokes equations of fluid dynamics and Maxwell's equations of electromagnetism. These differential equations must to be solved simultaneously, either analytically or numerically.

Galvanometer

A galvanometer is an instrument which is used to detect and measure small electric currents. It functions by the deflection of a magnetic compass needle by a current-carrying coil in a magnetic field.

Galvanometer mechanisms are utilized to position the pens of analog chart recorders like those used for making an electrocardiogram. Strip chart recorders with galvanometer driven pens have a full scale frequency response of 100 Hz and several centimeters deflection.

Sunday, April 12, 2009

Iris (eye anatomy)

The iris is an eye colored membrane which controls the amount of light that enters the eyeball and reach the retina by the contraction of its sphincter and dilator muscles. The iris is flat and divides the front of the eye into an anterior chamber posterior chamber. It is made of pigmented fibrovascular tissue called stroma.

The iris is divided into two zones: 1) pupillary Zone, which is the inner part of the iris that forms the pupil's boundary; 2) ciliary Zone, which is the remaining part of the iris that extends into the ciliary body.

The iris contains twy types of muscles. The sphincter muscle, which lies around the very edge of the pupil, contracts in bright light, causing the pupil to constrict. The dilator muscle, which runs radially through the iris, like spokes on a wheel, dilates the pupillary orifice in dim lighting.

Conjunctivitis

Conjunctivitis is an inflammation of the conjunctiva due to an allergic reaction or an infection caused by viruses or bacteria. Its symptoms are irritation, redness, and watering of the eye. When conjunctivitis is caused by bacteria, there is usually a yellowish mucopurulent discharge.

Conjunctivitis is not serious and can be cured with antibiotic-corticoid-containing drops, or with cool camomile tea eye wash.

Conjunctivitis is not serious and can be cured with antibiotic-corticoid-containing drops, or with cool camomile tea eye wash.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)